Science

The Monty Hall Problem: A Game Show’s Lesson for Gamblers

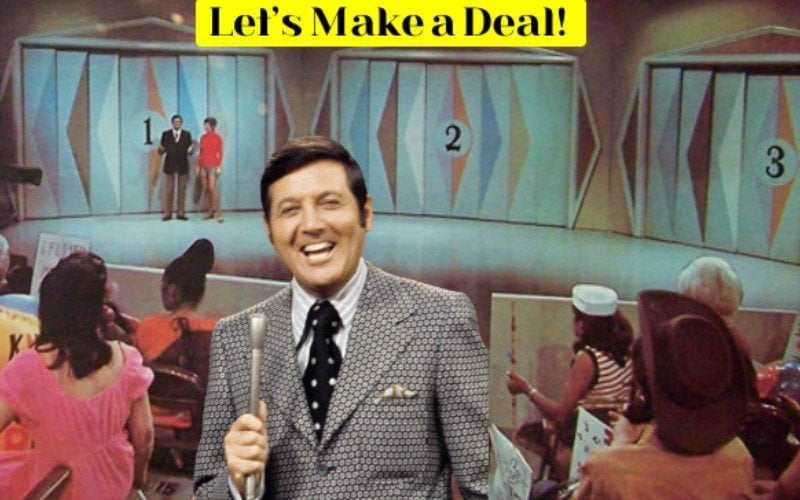

Let’s Make A Deal was one of the biggest gameshows in the US, with Canadian Monty Hall creating fantastic conundrums and puzzles. The most famous game on the show was the Monty Hall problem, where guests had to pick from one of three doors. Two of the doors had “non-prizes”, or nothing really worth winning. But behind one of the three, there was a brand new car, waiting to be won by a lucky contestant.

The game is not as simple as it seems at first glance. Monty Hall devised a fantastic puzzle where you could really increase your chances of winning. But the solution feels counterintuitive, and a prime example of how human instinct doesn’t always follow mathematical fact or logic.

What is the Monty Hall Problem

The game was presented with a now iconic quip:

“Do you want Door No. 1, No. 2, or No. 3?”

Monty Hall would ask guests to pick 1 of 3 doors, one of which had the grand prize. After they pick one, he would open another door, that revealed one of the non-prizes.

Then, the guest would have the chance to either stick with their initial door, or pick the last door. Hall always knew where the grand prize was, and always opened a door that didn’t have that prize.

Breaking Down the Probabilities

The basic assumption here would be that you have a 50-50 chance of winning because in the end, you have to pick between 2 doors. But that is not the case. The odds at the beginning are 1 in 3, and those odds remain even after the second door is opened. By swapping, you actually increase your chance of winning from 1/3 to 2/3. Let’s quickly break it down:

- Before a door is chosen, you have a 1 in 3 chance of winning

- Monty Hall strikes off one of the options, so you are left with a guess between 2 doors

- By sticking to your initial door, your chances remain 1 in 3

- When you swap, you go from a 1 in 3 chance, to the reciprocal, 2 in 3

Assume you pick the grand prize in the beginning, there is a 1 in 3 chance of doing so. In that case, by swapping you will lose. But there is a 2 in 3 chance of picking a non-prize, and swapping will automatically gift you the grand prize. The odds don’t change after the door is removed, but the game is designed to make contestants think their chances of winning go from 1/3 to 1/2.

How This Relates to Gambling

Monty Hall touched on a very important point for gamblers. The role of probability in casino games, and how we perceive our chances of winning. It shows how gut instinct can be counterintuitive, and that the mathematical odds are the only thing that is important for gamblers. Often, our instincts can work against us and lead to some players forming gambler’s fallacies during gameplay.

Typical Gambler’s Fallacy

Most fallacies are based on how we think about randomness and chance. We love to solve riddles or find solutions to problems, using logic or reason. But casino games don’t work that way. The results cannot be explained by any formula, you cannot use historical results to predict what will happen next.

The classic gambler’s fallacy uses historical data to predict what will happen in the next round. It is best explained with a simple two-way bet. Let’s say you are draw cards and bet on whether they will be red or black. There are 52 cards in a standard deck, 26 of which are red and 26 black. This means the chances of drawing either red or black is 50-50. To make it perfectly fair, the deck is always reshuffled after every draw, thus the already-drawn cards are not taken out of the game.

Let’s say you then draw 6 black cards in a row. The gambler’s fallacy is to believe that there is a greater chance of the 7th card being red. After all, the odds of drawing black 7 times in a row is 1 in 128 (2 to the power of 7). However, that is no the way it works. The odds are always 1 in 2 at the beginning of every draw. The results may be quite unlikely, but they are completely random. You are not “overdue” a red to balance the outcomes.

How Variance Affects Probability

Yet if we were to keep playing for millions of rounds, the number of red and black wins would start to balance out. The more rounds you simulate, the greater the chance that the outcomes will closely resemble the actual probabilities of either winning. The key word here is variance. Variance is the measurement of how much the results deviate from the real odds of winning. For instance, if you play 25 rounds of French Roulette and win 2 straight up bets (1 in 37 chance), variance is working in your favor. With no variance, you should realistically only win once in every 37 rounds, not twice in 25.

Variance can also form winning or losing streaks. Such as the red/black conundrum above. Drawing 6 blacks in a row is a big deviation from the 50-50 chances of winning. Which would otherwise suggest that the results should alternate between red and black. In the short run, variance is generally a lot higher. After simulating millions of rounds (Monte Carlo Method), you reduce the likelihood of statistical anomalies and fluke results distorting the outcomes. The results will become more balanced, in proportion to the mathematical odds.

Thinking that the outcomes should balance out is a gambler’s fallacy. Yet backing the variance is also a fallacy. For example, thinking the blacks are on a losing streak and from now on you should stick to betting on reds. It can even occur in sports betting, when a team is in good form and winning most games. The hot hand fallacy examines the phenomena when players buy into winning streaks, or believe that some outcomes are more likely to occur in spite of the mathematical odds.

How the Element of Control Changes Everything

Games such as blackjack, poker, and video poker introduce an element of control. You can directly influence the outcome in these games, and with expert strategies, skilled players can reduce the house edge. But that does not take away the fact that the games run on chance, and no matter how good you get, you will still need luck on your side.

One typical fallacy associated with these games is the belief that expert strategies are infallible. After all, you use mathematically optimised responses to make the most of any hand you are dealt. But in poker, you can still lose on a winning hand. Or in blackjack, you can go bust, or lose to the dealer if you don’t draw the most likely cards. These strategies will most likely enhance your chances of winning, but they don’t rule out the possibility that over the long run, you will lose. Because let’s face it, casino games are designed to always give the house an edge. The most likely scenario is that eventually, you will lose your money.

Counterintuition and Instinct vs Logic

Going back to Monty Hall for a minute, and there are some parallels between his game and counterintuition in these “skill based” games. For instance, in video poker strategies, the best response is always to aim for the biggest payouts. Even if you have already got a low-paying poker hand, if you are 2 cards short of hitting the Royal Flush, you should ditch the guaranteed smaller win to test your luck making the big win. In most cases, it won’t pay off, but you only need the variance to swing your way once to come away with a handsome payout.

Or in blackjack strategies, 12 out of 13 times you are told to double down if you have a value of 10 or 11. The only time you should just hit is when the dealer has Ace, in which case they may draw a Blackjack. But otherwise, you should double your stake and hit. But there is a 4 in 13 chance you will only get up to 16 – at which case the dealer can still draw cards and beat you.

Yet the logic is that 4 out of 13 times you will draw 10 and get a score of 20 or 21. And there is a chance your 16, 17, 18, or 19 can still beat the dealer, or force them to go bust. But it doesn’t rule out the risk of losing.

Play Smarter and Always Remember the Odds

At the end of the day, the casino will always have an edge. The maths says gambling is a losing game. When you play, you cannot rule out the fact that the odds are stacked against you, and the probability points towards you losing your money.

Yet anything can happen, and with a fortuitous run of variance, you could finish on a high. You may play blackjack for an hour and come away with double your initial bankroll. Or, play slots for an hour and win next to nothing. And then suddenly hit a gigantic jackpot, not just cutting your losses to 0, but putting you thousands of dollars up in the green.

The important thing to remember is that variance can come at any time. You are in charge of two things when you gamble. How much you play with – determining how long you can play before going bust. And the second is when you decide to quit. You must be able to sustain a longer gaming session to catch any good variance, but also be ready to quit while you are ahead, something that gets easier with practise.